Umberto Angeloni, ancien CEO de Brioni, CEO de Caruso & créateur de Uman, a accepté de poursuivre sur BrandWatch ses réflexions sur l'avenir des marques de luxe et du retail qu'il a initié en juin 2011 avec "Retailing Luxury in a Reset World".

Umberto Angeloni, ancien CEO de Brioni, CEO de Caruso & créateur de Uman, a accepté de poursuivre sur BrandWatch ses réflexions sur l'avenir des marques de luxe et du retail qu'il a initié en juin 2011 avec "Retailing Luxury in a Reset World".

Il porte aujourd'hui sa réflexion sur l'importance de la nationalité d'une marque. Il prend appui sur l'exemple chinois, en montrant que le développement de marques de luxe chinoises est inéluctable et que les business models pour y arriver sont nombreux et innovants.

In a recent announcement, the Chinese government has prohibited all TV programs that promote: “excessive entertainment and vulgar tendencies”, and earlier last year all outdoor advertising of “foreign things” and “hedonistic, high-end lifestyle” had been banned from Beijing.

Although these moves appear to be motivated mainly by politics – in the face of growing inequality and creeping corruption, several upcoming leaders are now paying lip service to Maoism – there is nevertheless a popular sentiment of resurging nationalism, while the government is trying to redirect domestic consumption towards local creativity and crafts. In the context of such rather unusual events, how long will it be before authorities start curbing imports of global luxury brands that appear to encourage, say: “opulent consumption and offensive luxury”, or prohibit them from opening more than one shop per city? Several multinational companies (MNCs) are taking this scenario as a real possibility.

The sentiment among Chinese state-planners, executives and even consumers, is that the largest marketplace in the world cannot be forever slave to imported lifestyle goods and that all the rich cultural heritage of the nation should be able to generate domestic luxury brands.

I am not talking about “designer brands” or “ethnic brands”, they already exist in many countries and some even enjoy a bit of an international cachet. We are also well past the model of fake “Italian” brands made in China, while the surrogates offered by the global brands – a phenomenon that I would define as “adaptation” or “affiliation” – look more like defenses rather than solutions.

This is about a genuine Chinese luxury brand created for the affluent and educated Chinese, with the blessing of the establishment. But with a major difference: that in order to be qualified as haut de gamme, it has to employ certain aesthetic inputs and to apply specific production processes and incorporate special materials that are today indispensable to a luxury product. All of these must come from the original “country-of-excellence”, which in the case of menswear is Italy. Since the company launching the brand is ultimately government-controlled and serving the military, this will be a “power suit” in every sense of the word.

What are the implications of this new formula, and why is it innovative?

- It assumes that its target consumers (the affluent and educated Chinese) have evolved enough to be able to appreciate the value of the product, the integrity of the process and the authenticity of its provenance; and this is happening much faster than in other new markets (in Japan it took more than twenty years). On the contrary, although even in the Chinese market the Modern Rich is becoming prevalent, most luxury brands still take the nouveau riche as its ideal target: naïve and ready to exploited.

- It is managed like a niche luxury brand: not meant to proliferate into a massive mono-brand retail chain or into all kinds of brand extensions, diffusion lines and wholesale channels. The plan is: one shop at a time, with the first one in Beijing next year.

- it is fully transparent about the origin of the product: in fact it even discloses the name of the maker (Caruso) as a competitive advantage; this is an intelligent approach, which recognizes the fact that there are now just a handful of manufacturers left in Italy who can deliver the level of quality and complexity that true luxury products require. Most global brands still want to give the consumer the illusion that they directly manufacture all that they sell, and deny vehemently whenever the truth emerges.

- it teaches many so-called luxury brands a lesson about integrity, especially some Italian ones that have abandoned the “Made-in-Italy”, in favor of some formulaic versions of made-by-brand or made-in-brand that mask the partial loss of “insourcing”.

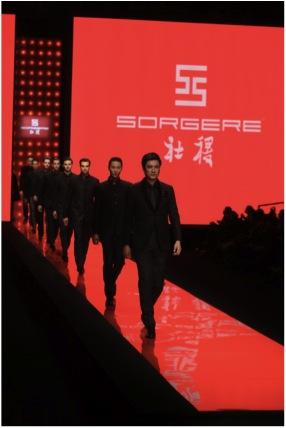

Beijing Fashion Week - March 30th 2012 - Beijing Hotel - Beijing

The only factor apparently missing from SheJi is the fabled “heritage” of global luxury brands. Yet the concept of addressing a cultural Sinosphere that spans the globe seems well grounded, and can give it a significant advantage in the local market. If proven a success, it could potentially be followed by other “national brands” in major new markets for luxury goods, such as India. The international press has already understood the historical relevance of this event, and it has covered it extensively in just the past six months – BusinessWeek, the Financial Times, Welt Am Sonntag, to name a few – Chinese blogs and forums, and even the official “People’s Daily”. But perhaps none other than global luxury brands should pay more attention, as their apparent dominance and seemingly unlimited growth potential in China may soon be affected by this cultural phenomenon and the underlying forces that have started it.